Jag gillar när människor reflekterar och sammanfattar sina lärdomar, det är en koncentration eller destillering av åratals kunskap, misstag och erfarenheter. Här är en bra artikel:

Nedan är rubrikerna

Risk cannot be destroyed, only transformed.

“No pain, no premium”

Diversifying, cheap beta is worth just as much as equally diversifying, expensive alpha.

Diversification has multiple forms.

The philosophical limits of diversification: if you diversify away all the risk, you shouldn’t expect any reward.

It’s usually the unintended bets that blow you up.

It’s long/short portfolios all the way down.

The more diversified a portfolio is, the higher the hurdle rate for market timing.

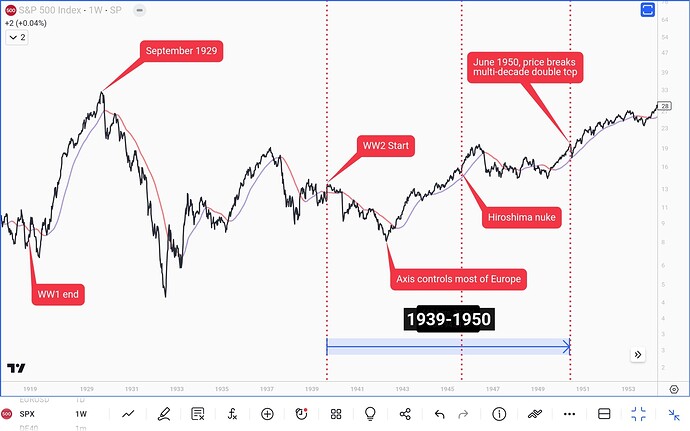

Certain signals are only valuable at extremes.

Under strong uncertainty, “halvsies” can be an optimal decision.

Always ask: “What’s the trade?”

The trade-off between Type I and Type II errors is asymmetric

Behavioral Time is decades longer than Statistical Time

Jensen’s Inequality

A backtest is just a single draw of a stochastic process.

The Market is Usually Right

Några citat som stack ut:

Ultimately, when you build a portfolio of financial assets, or even strategies, you’re expressing a view as to the risks you’re willing to bear.

I’ve come to visualize portfolio risk like a ball of play-doh. As you diversify your portfolio, the play-doh is getting smeared over risk space. For example, if you move from an all equity to an equity/bond portfolio, you might reduce your exposure to economic contractions but increase your exposure to inflation risk.

The play-doh doesn’t disappear – it just gets spread out. And in doing so, you become sensitive to more risks, but less sensitive to any single risk in particular.

samt

The philosophy of “no pain, no premium” is just a reminder that over the long run, we get paid to bear risk. And, eventually, risk is likely going to manifest and create losses in our portfolio. After all, if there were no risk of losses, then why would we expect to earn anything above the risk-free rate?

So, almost by definition, certain strategies – especially low frequency ones – need to be difficult to stick with for any premium to exist. The pain is, ultimately, what keeps the strategy from getting crowded and allows the premium to exist.

samt

For example, if you invest only in stocks, finding a way to thoughtfully introduce bonds may do much, much more for your portfolio over the long run, with a higher degree of confidence, than trying to figure out a way to pick better stocks.

For most portfolios, beta will drive the majority of returns over the long run. As such, it will be far more fruitful to first exhaust sources of beta before searching for novel sources of alpha.

och

One of the most common due diligence questions is, “when doesn’t this strategy work?” It’s an important question to ask for making sure you understand the nature any strategy. But the fact that a strategy doesn’t work in certain environments is not a critique. It should be expected. If a strategy worked all the time, everyone would do it and it would stop working.

och

A corollary to this point is what I call the frustrating law of active management. The basic idea is that if an investment idea is perceived both to have alpha and to be “easy”, investors will allocate to it and erode the associated premium. That’s just basic market efficiency.

So how can a strategy be “hard”? Well, a manager might have a substantial informational or analytical edge. Or a manager might have a structural moat, accessing trades others do not have the opportunity to pursue.

But for most major low-frequency edges, “hard” is going to be behavioral. The strategy has to be hard enough to hold on to that it does not get arbitraged away.

Which means that for any disciplined investment approach to outperform over the long run, it must experience periods of underperformance in the short run.

But we can also invert the statement and say that for any disciplined investment approach to underperform over the long run, it must experience periods of outperformance in the short run.

samt

I once read a comic – I think it was Farside, but I haven’t been able to find it – that joked that the end of the world would come right after a bunch of scientists in a lab said, “Neat, it worked!”

It’s very rarely the things we intend to do that blow us up. Rather, it’s the unintended bets that sneak into our portfolio – those things we’re not aware of until it’s too late.

och

Market timing is probably finance’s most alluring siren’s song. It sounds so simple. Whether it’s market beta or some investment strategy, we all want to say: “just don’t do the thing when it’s not a good time to do it.”

samt

I spent months agonizing over the right way to do things. I read papers. I did empirical analysis. I even took pen to paper to derive the expected factor efficiency in each approach.

At the end of the day, I could not convince myself one way or another. So, what did I do? Halvsies.

Half the portfolio was managed in a mixed manner and half was managed in an integrated manner.

Really, this is just diversification for decision making. Whenever I’ve had a choice with a large degree of uncertainty, I’ve often found myself falling back on “halvsies.” When I’ve debated whether to use one option structure versus another, with no clear winner, I’ve done halvsies.

When I’ve debated two distinctly different methods of modeling something, with neither approach being the clear winner, I’ve done halvsies.

Halvsies provides at least one step in the gradient of decision making and implicitly creates diversification to help hedge against uncertainty.

och

It’s just simply acknowledging that managing money in real life is very, very, very different than managing money in a research environment.

It is easy, in a backtest, to look at the multi-year drawdown of a low-Sharpe strategy and say, “I could live through that.” When it’s a multi-decade simulation, a few years looks like a small blip – just a statistical eventuality on the path. You live that multi-year drawdown in just a few seconds in your head as your eye wanders the equity curve from the bottom left to the upper right.

In the real world, however, a multi-year drawdown feels like a multi-decade drawdown. Saying, “this performance is within standard confidence bands for a strategy given our expected Sharpe ratio and we cannot find any evidence that our process is broken,” is little comfort to those who have allocated to you. Clients will ask you for attribution. Clients will ask you whether you’ve considered X explanation or Y. Sales will come screeching to a halt. Clients will redeem.

och

As the saying goes, nobody has ever seen a bad backtest.

samt avslutningsvis:

This final lesson is about a mental switch for me. Instead of seeing something and immediately saying, “the market is wrong,” I begin with the assumption that the market is right and I’m the one who is missing something. This forces me to develop a list of potential reasons I might be missing or overlooking and exhaust those explanations before I can build my confidence that the market is, indeed, wrong.

Ping @zino, @Andre_Granstrom, @AllSeasonsPortfolio, @jfb, @Marknadstajmarn m.fl.